SITUL BILINGV KINOGLAZ (ENG.+FRANC.) - SURSA FIABILA DE INFORMATIE CINEFILA

http://www.kinoglaz.fr/u_fiche_film.php?lang=fr&num=9708

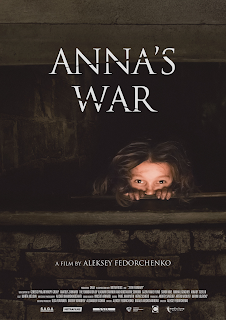

Alekseï FEDORTCHENKOАлексей ФЕДОРЧЕНКОAleksey FEDORCHENKORussie, 2018, 73 mnfiction | La Guerre d'Anna▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪ ▪Война АнныAnna's warVoyna Anny |

Réalisation : Alekseï FEDORTCHENKO (Алексей ФЕДОРЧЕНКО)

Scénario : Alekseï FEDORTCHENKO (Алексей ФЕДОРЧЕНКО), Natalia MECHTCHANINOVA (Наталия МЕЩАНИНОВА)

Interprétation

Marta KOZLOVA (Марта КОЗЛОВА)

Images : Alicher KHAMIDKHODJAEV (Алишер ХАМИДХОДЖАЕВ)

Décors : Olga GOUSSAK (Ольга ГУСАК), Alekseï MAXIMOV (Алексей МАКСИМОВ), Larissa MEKHANOCHINA (Лариса МЕХАНОШИНА)

Musique : Vladimir KOMAROV (Владимир КОМАРОВ)

Montage : Pavel KHANIOUTINE (Павел ХАНЮТИН)

Produit par : Andreï SAVELIEV (Андрей САВЕЛЬЕВ), Artiom VASSILIEV (Артем ВАСИЛЬЕВ), Dmitri_2 VOROBIEV (Дмитрий_2 ВОРОБЬЕВ)

Production : 29th February Film Company; Метрафильмс / Metrafilms; Saga

Site : Page IMDb

Prix et récompenses :

Meilleur film Prix de l'Aigle d'or, Moscou (Russie), 2019

Meilleure réalisation Alekseï FEDORTCHENKO , Prix de l'Aigle d'or, Moscou (Russie), 2019

Meilleur film Prix "NIKA", Moscou (Russie), 2019

Meilleur rôle féminin Marta KOZLOVA , Prix "NIKA", Moscou (Russie), 2019

Meilleur film Prix de la Guilde des historiens et critiques de cinéma, Moscou (Russie), 2018

Meilleure image Alicher KHAMIDKHODJAEV , Prix de la Guilde des historiens et critiques de cinéma, Moscou (Russie), 2018

Meilleur rôle féminin Marta KOZLOVA , Prix de la Guilde des historiens et critiques de cinéma, Moscou (Russie), 2018

A noter :

La Guerre d’Anna est exempt de tout dialogue et présente la guerre à travers les yeux d’une fillette juive qui, traumatisée par la mort de ses parents, se cache dans la cheminée de l’école, transformée par les nazis en kommandantur. Dans les limites du monde perceptible par elle, cette œuvre exacerbe l’ensemble de nos sens, lorsque chaque rayon de lumière, bruissement, fragment de conversation étrangère devient un signal de danger ou d’espoir. Le scénario, la réalisation, le travail de cadrage, et le jeu de Marta Kozlova, âgée de 6 ans seulement, font de ce film un véritable chef-d’œuvre, qui a d’ores et déjà été nominé pour le prix de l’Académie européenne du cinéma.https://fr.rbth.com/art/81841-femmes-cinema-russie-festival-honfleur

Synopsis

Toute la famille de l’héroïne a péri dans un massacre de masse. Elle-même est restée en vie par miracle grâce à sa mère qui l’a couverte de son corps. Pendant plus de deux ans la fillette juive a vécu dans une cheminée inutilisée de la kommandantur jusqu'à ce que le village soit libéré des nazis. Cela paraît incroyable mais Anna réussit non seulement à survivre mais à garder son humanité. Elle est aidée en cela par le souvenir de ses parents, de sa maison et également par son ami qui la sauve d'une totale solitude.

Commentaires et bibliographie

Aleksei Fedorchenko: Anna’s War (Voina Anny, 2018), Andrei ROGATCHEVSKI, Critique de film, Kinokultura, 2019

===========================

CLIK DREAPTA -SELECTEAZA COMANDA TRADUCERE IN ROMANA

Issue 63 (2019) |

Aleksei Fedorchenko: Anna’s War (Voina Anny, 2018) reviewed by Andrei Rogatchevski © 2019 |

Anna is a six-year old Ukrainian-Jewish girl, whose parents were shot in the Holocaust. She survives a mass execution unharmed and for months and months hides inside a large disused fireplace in a countryside school, converted into a Nazi commandant’s office. With only a stray cat for company, at night (when the school is empty), Anna drinks water from flower bowls and paintbrush cans, eats bait from rat traps and starch from bookbinding cloth, and keeps herself warm by wearing animal fur off an effigy. By day, she quietly observes the office routine (including beatings, partying and love-making) from behind the fireplace mirror. Her alternative reality is populated with inhuman creatures, such as flayed mannequins from anatomy classes and guisers at a Christmas celebration.

Anna’s luck gets her out alive from the chance encounters with a drunk Nazi, who mistakes her for a child invitee to this celebration (held in the school building)—and a partisan, who intends to blow the commandant’s office up by leaving a time bomb in the fireplace. Gradually, Anna’s survival skills are honed to such a degree that she begins to supplement her diet by catching and roasting pigeons from the school attic. She also masters the art of fighting back—and surreptitiously poisons to death a Nazi guard dog for killing her cat. Ultimately, she even gains a symbolic victory over Nazi Germany by moving pins on a World War II situation map, all at once, from their rightful place to Germany’s pre-war territory, as if in a séance of white witchcraft.

Anna’s War is apparently based on a true story (see Barabash 2018) and spares no effort to look believable. The screenplay takes into account the medical data on how long can a six-year old live without water, food, going to the bathroom, etc. The props (such as school textbooks and specimen jars) are authentic (or close imitations of) historical objects. As the action is supposed to take place in the Poltava region, on a crossroads of a world war theatre, multilingual speech is heard from time to time, not only in Yiddish, German, Russian or Ukrainian, but also in French, Romanian and Hungarian.[1] Anna herself does not utter a single word throughout, though. This highly demanding role—a cross between Anne Frank and Alice through the Looking-Glass, Soviet-style (Dolin 2018)—is compellingly played by Marta Kozlova, who was six years of age when the filming began.

At the Q&A with the crew after the film’s screening at the Regent Street Cinema (London) in November 2018 (as part of the UK’s Russian Film Week festival), the audience was told that Marta had been treated as an adult member of the team from the outset. Once she had learnt about World War II and Holocaust, it was not too difficult for her to fit in. A week into the shooting, Marta reportedly developed an identification with Anna’s character to such an extent that she even tried to influence the filmmaking process by claiming that Anna would not have done some of the things laid out for her in the script. A Screen Daily reviewer, who had seen Anna’s War at the International Film Festival in Rotterdam in Winter 2018, called Marta’s performance “mesmerizing” (Ide 2018).

An example of what might be termed Holocaust Light for its moderate scale and tactful removal of violent scenes off the screen, Anna’s War is a worthy feature-long fictional companion to Fedorchenko’s earlier and shorter (but no less powerful) documentary effort David (2001), which is also about a Holocaust child survivor (for more on it, see Karchevskii 2008). In a conversation with me in November 2018 in London, Fedorchenko said that he would like both films to be shown together, under the joint title David and Anna. This would probably be a desirable double bill for school and family screenings on International Holocaust Remembrance Day for many years to come.

However, not everyone has been impressed with Anna’s War. A Variety reviewer opined that it was a “tedious tale, […] more a patience tester than a poignant rollercoaster ride. […] Each of Anna’s actions provokes incredulity rather than distress” (Weissberg 2018). Yet, needless to say, in order to be good, feature films do not necessarily have to entertain, or pass a strict test for historical accuracy, or possess common-sense plausibility. Besides, Anna’s War’s significance is not limited to Holocaust representation. Cinephiles and industry professionals are bound to admire the film’s ingenious solution of a challenging technical task, namely Alisher Khamidkhodzhaev’s shooting in a claustrophobically tight space.

During the filming, Marta would be instructed to sit in the fireplace for hours doing nothing, while the DoP would stand next to her with a camera capturing her occasional movements. Some of these shots were later included in the final cut, functioning as a pars pro toto. According to The Hollywood Reporter, Fedorchenko was “clearly trying to condense the entirety of the war into the smallest setting possible, revealing how one minute experience can speak volumes about the rest” (Mintzer 2018). For his part, Dolin (2018) defines Anna’s War as “minimalist and epoch-making at the same time”.

Film aficionados can draw visual parallels between Anna’s War and other memorable motion pictures, such as Agnieszka Holland’s In Darkness (W ciemności, 2011; about Jews hiding in a Lviv sewer during the Nazi occupation), Andrzej Wajda’s A Love in Germany (Eine Liebe in Deutschland, 1983; contains a frame of a child licking a swastika-decorated lollypop, similar to Anna eating a Christmas party leftover in the form of a swastika-shaped cookie) and Roman Balaian’s Lone Wolf (Biriuk, 1977; made almost entirely without a dialogue, by recourse to self-explanatory mise-en-scènes and diegetic field and Foley recordings).

Over and above its sophisticated cinematic accomplishments and all-important historical setting, Anna’s War seems to be projecting a transcendent message about the power of the powerless (to borrow Václav Havel’s expression): at a time when a malevolent force dominates over parts of the world, the almost invisible and ostensibly negligible opponents of this force can quietly summon sufficient strength to defeat it—if luck is on their side and they are resourceful enough.

Notes

1] The film’s international ambience was greatly assisted by its postproduction team, which included a Japanese composer, a French editor and a French-Bosnian-Indian-British team of sound designers. A Yiddish song called “Hungerik dayn ketsele” (Your hungry kitten), by the Polish Jewish poet and songwriter Mordechai Gebirtig (1877–1942), a Holocaust victim, was used in the soundtrack to a great emotional effect.

Andrei Rogatchevski

UiT – the Arctic University of Norway

| Comment on this article on Facebook |

Works Cited

Barabash, Ekaterina. 2018. “Aleksei Fedorchenko: ‘Fil’mom Voina Anny ia zakryl temu Vtoroi mirovoi’.” RFI.fr 31 January.

Dolin, Anton. 2018. “Voina Anny Alekseia Fedorchenko: Pochemu novyi fil’m rezhissera Ovsianok i Angelov revoliutsii—odin iz luchshikh v 2018 godu.” Meduza 30 January.

Ide, Wendy. 2018). “Anna’s War: Rotterdam Review.” Screen Daily 28 January.

Karchevskii, Lev. 2008. “Nazad, v SSSR!” Lekhaim (Moscow), January.

Mintzer, Jordan. 2018. “Anna’s War (Voina Anny): Film Review / Rotterdam 2018.” The Hollywood Reporter 1 February.

Weissberg, Jay. 2018. “Rotterdam Film Review: Anna’s War.” Variety 6 February.